Four years after euthanasia was legalised throughout Canada on 17 June 2016 the “first annual report” covering euthanasia deaths in 2019 was released in July 2020.

As the dead bodies pile higher – 13,946 of them in three and a half years according to the report – there are at least nine lessons to be learned for other jurisdictions considering legalising euthanasia or assisted suicide.

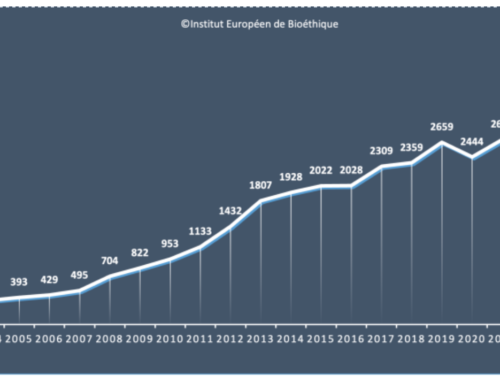

1. Once euthanasia is legalised numbers continue to increase from year to year

The report states that there were 5,631 cases of euthanasia and assisted suicide under the Canadian law in 2019, with a total of 13,946 cases since legalisation.

Cases increased by 57% from 2017 to 2018 and by 26% from 2018 to 2019.

Euthanasia and assisted suicide accounted for 1.96% of all deaths in Canada in 2019, 2.4% in Quebec and 3.3% in British Columbia.

2. Where both are offered euthanasia is preferred to assisted suicide and the overall rate is higher than where assisted suicide only is offered

Less than seven of the 5,631 cases in 2019 were assisted suicide.Canadian practice overwhelming uses euthanasia.The report states that “providers are less comfortable with self-administration [assisted suicide] due to concerns around the ability of the patient to effectively self-administer the series of medications, and the complications that may ensue”.

Euthanasia deaths accounted for 1.96% of all deaths in Canada in 2019 – four times the rate in Oregon, where assisted suicide accounted for 0.5% of all deaths in 2019.

3. Broadening access

Although 66% of cases of euthanasia in Canada in 2019 involved a person with cancer, there were also 9.1% of cases for “multiple comorbidities”, which may be code for what the Dutch call “a stack of old aged disorders”, and 6.1% of all cases as performed for “other conditions”, which “includes a range of conditions, with frailty commonly cited”.

4. Lack of specialist involvement

Despite two thirds of cases with cancer as the underlying condition, only 1.7% of clinicians administering euthanasia gave their specialty as oncology. The majority (65%) of those administering euthanasia were primarily engaged in family medicine.

Oddly, given euthanasia is not yet officially permitted in Canada for psychiatric conditions, 1.2% of cases of euthanasia were administered by psychiatrists.

5. Doctors who kill … a lot

The report also notes that among those administering euthanasia were “a small number of practitioners identifying themselves as “MAID Providers.” While this specialty is not officially recognized by medical certifying bodies in Canada, it may be considered a functional specialty by some providers when MAID is the primary focus of their practice.”, that is there are doctors whose primary practice is euthanasia.

Of the 1196 physicians and 75 nurse practitioners who euthanased people in 2019, some 126 of them did so 10 times or more.

6. Coercion or lack of voluntariness can be missed

The report states that in “virtually all cases where” euthanasia “was provided, practitioners reported that they had consulted directly with the patient to determine the voluntariness of the request for” euthanasia.

Table 6.3 indicates that “virtually all” means 99.1% of the 5389 cases for which this information was provided.

This means that in 46 cases the practitioner who administered euthanasia admitted that they did NOT consult directly with the person he or she euthanased to “determine the voluntariness of the request”.

7. Decision making capacity not properly assessed

Of 5,389 people killed by euthanasia in Canada in 2019 for whom data is available on the length of time between first request and when euthanasia was administered some 34.3% or 1,578 people were euthanased in less than 10 days of first requesting it.

This is allowed under Canada’s law for only two reasons: death is expected within 10 days or loss of decision making capacity is expected within 10 days (or both).

For 909 (17%) of these people the only justification given for the haste with which euthanasia was performed was that loss of capacity to consent was imminent.

This raises real questions about the validity of the original request.

If a person is on the verge of losing capacity what degree of certainty can there be that the person currently has full capacity?

8. Not a last resort

The report reveals that in at least 91 cases of euthanasia palliative care was NOT accessible if needed.

In at least 87 or 3.9% (but possibly in at least 227 or 10.2%) of cases disability support services were NOT provide although they were needed.

“Disability support services could include but are not limited to assistive technologies, adaptive equipment, rehabilitation services, personal care services and disability based income supplements.”

The report admits that even for those who were reported as having received disability support services the data “does not provide insight into the adequacy of the services offered”.

This reality is illustrated in the case of Roger Foley

9. Euthanasia is chosen for loneliness or feeling a burden on family

The report states that “Loss of ability to engage in meaningful life activities (82.1%) followed closely by loss of ability to perform activities of daily living (78.1%), and inadequate control of symptoms other than pain, or concern about it (56.4%) were the most frequently reported descriptions of the patient’s intolerable suffering.”

Disturbingly 34% reported as a reason for their euthanasia request “Perceived burden on family, friends or caregivers” and 13% reported “Isolation or loneliness”.