To view a PDF of this document, click here.

There are major ethical violations associated with a new medical technique called Normothermic Regional Perfusion, developed in Spain and elsewhere in Europe, notably the United Kingdom, and now in use in the United States. This intervention keeps oxygenated blood flowing to the organs of donors, with the notable exception of the brain, in order to optimize their quality for transplantation.

Several conditions apply for organ donation if it is to meet ethical standards. Donation must come as a free gift that is uncoerced. The decision must be made with the informed consent of the donor or the authorized medical proxy. The transplants of hearts, or other organs which a person needs to stay alive, can only happen after the donor has died. The Dead Donor Rule is ethically essential because the act of removing a heart or both lungs would kill the donor.

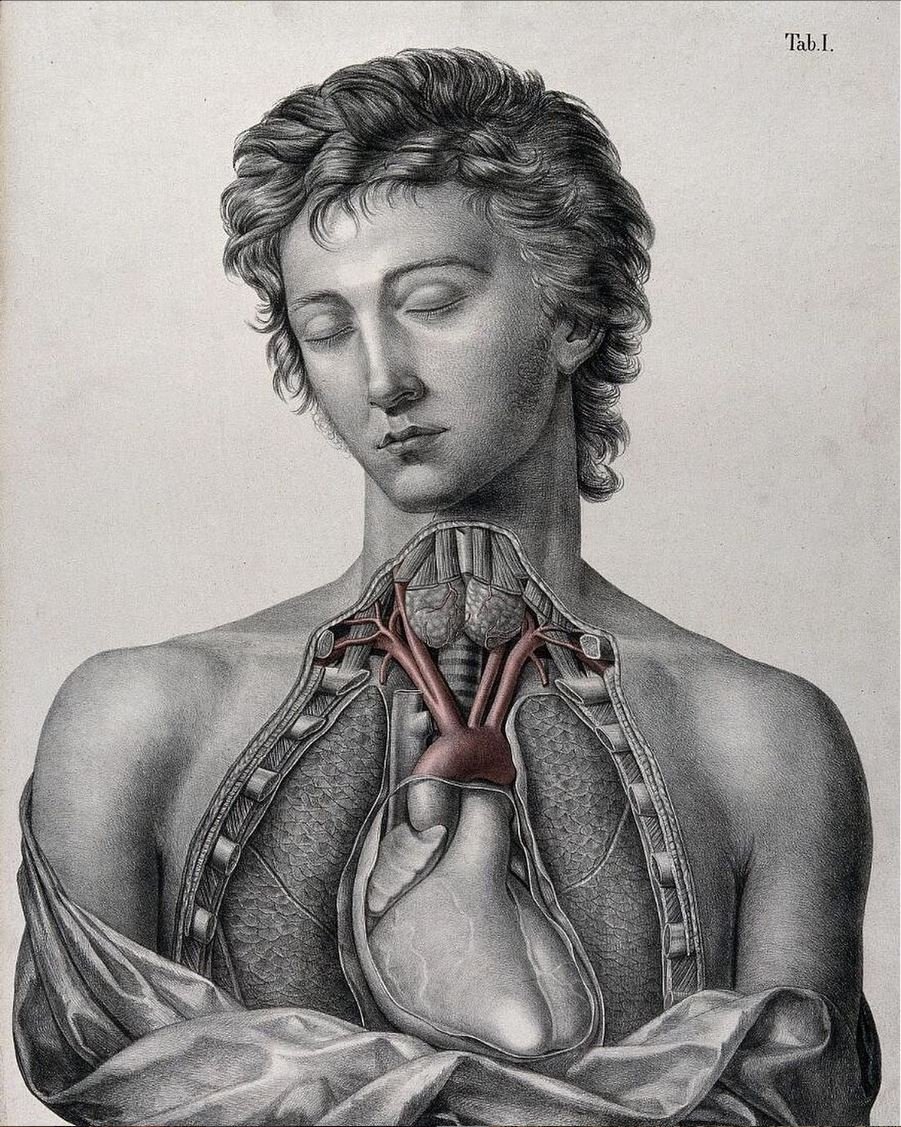

This is a description of this new technique. The donor’s heart stops beating, and the medical team waits a certain number of minutes (protocols differ from two to five minutes). The person is then declared dead by cardiac criteria and Normothermic Regional Perfusion follows. Almost unbelievably, the transplant team clamps off the major blood vessels to the brain and arms to ensure the person’s brain will die due to lack of oxygenated blood. Then circulation of oxygenated blood is restarted using a heart lung bypass machine like those used in open heart surgeries. This is either done for the thoracic-abdominal area or just the abdominal area of the body, depending on which organs will be taken for transplantation.

The rationale is that donors do not revive after declaration of cardiac death because they are on bypass technology and now fulfill the criteria for brain death. The heart and lungs’ functions have been taken over by machines and the technicians make sure the brain lacks oxygen by clamping off arteries. This is terrible to contemplate.

Irreversible cessation of key bodily functions is a fundamental characteristic of death. If a person can be resuscitated, he is not dead yet. It is true that those whose hearts have stopped for two to five minutes are dying, but if they can be brought back this is proof that they were not dead. If we know scientifically that there is a good chance of resuscitating a patient following cardiac arrest and cessation of breathing after five minutes, then ethically one must wait longer to be able to truly declare death.

The reason for the rush to declare death through convoluted procedures like Normothermic Regional Perfusion is organ harvesting. Tissues and organs begin to deteriorate and die when deprived of oxygen. The longer one waits, the more the organs are damaged and the less chance there is of a successful transplantation. Donors with a diagnosis of brain death are much preferred for transplantation because their organs are perfused with blood right up to the moment of excision. The problem is that few potential donors fit the neurological criteria of irreversible cessation of all brain activity. What Normothermic Regional Perfusion does is artificially create more persons who fit brain death criteria.

It is unacceptable to play fast and loose with declaring persons to be dead in order to procure more and better-quality organs for transplantation. Respect for the dignity of the human person requires moral certitude of death before any transplanting of vital organs can take place. I fear that the intense desire to obtain transplantable organs is leading some to declare donors dead who are not yet dead. Worse still, Normothermic Regional Perfusion provokes death through arterial clamping and a too rapid declaration of death by cardiac criteria.

Good bioethics and technical efficiency in organ transplantation are in conflict when it comes to strange interventions like Normothermic Regional Perfusion. Those who thought this up must have reasoned that ethics and the law do not permit doctors to ignore the Dead Donor Rule. Their objective, however, was to circumvent a true declaration of death in favor of minimum standards that are not certain at all. Although the patient’s heart might still be revived, they get around the problem by using heart-lung bypass technology. If a person can be resuscitated, it is proof he was not dead yet.

This, I think, is why there are proposals to change the cardio-pulmonary criteria for death from “irreversible” cessation of cardiac function and breathing to “permanent” cessation. Some claim that all that is needed for death is that the person will not spontaneously revive, not that it is impossible to medically revive them. With advances in scientific techniques for resuscitation, there are more patients who can be revived today. It can be ethical in some circumstances to allow persons to die without employing every means at our disposal to resuscitate them, but it is never ethical to declare a person dead who is merely in the process of dying.

Joseph Meaney became president of the NCBC in 2019. He received his PhD in bioethics from the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Rome; his dissertation topic was Conscience and Health Care: A Bioethical Analysis. Dr. Meaney earned his master’s in Latin American studies, focusing on health care in Guatemala, from the University of Texas at Austin. His bachelor’s degree was in history from the University of Dallas. Dr. Meaney was director of international outreach and expansion for Human Life International (HLI) and is a leading expert on the international pro-life and family movement, having traveled to eighty-one countries on pro-life missions. He founded the Rome office of HLI in 1998 and lived in Rome for nine years, where he collaborated closely with dicasteries of the Holy See, particularly the Pontifical Council for the Family and the Pontifical Academy for Life. He is a dual US and French citizen and is fluent in French, Spanish, Italian, and English. His family has been active in the health care and pro-life fields in Corpus Christi, Texas, and in France for many years.