Here is the statement given by Archbishop Anthony Fisher OP on Friday 10 December to the NSW parliamentary inquiry into euthanasia.

Thank you for the opportunity to address the Committee this morning.

I appear on behalf of the Catholic Bishops of NSW and the Bishops of the Australasian‐Middle East Christian Apostolic Churches. The faithful of our communities make up a quarter of the population of this state.

The Catholic Church in NSW operates 11 hospitals and 59 nursing and aged care facilities, each of which is directly affected by this bill. The Catholic faithful also provide a significant proportion of the state’s healthcare workforce.

Catholic health and aged care institutions are founded on the belief in the sanctity of human life and the inalienable dignity of the person.

“LEGALISING EUTHANASIA AND ASSISTED SUICIDE WILL BE A RADICAL DEPARTURE FROM ONE OF THE FOUNDATIONAL PRINCIPLES OF OUR SOCIETY.”

The proposition that human life is inviolable has been part of the common morality of the great civilisations, the best secular philosophies, the common law, international human rights documents, pre-Christian Hippocratic ethics, the codes of the World Medical Association and the Australian Medical Association, and the world’s great religions.

Unsurprisingly, we oppose any attempt to legalise euthanasia or assisted suicide in this state. Our opposition is based not only on religious beliefs, but also upon the desire to protect the most vulnerable in our society.

Legalising euthanasia and assisted suicide will be a radical departure from one of the foundational principles of our society.

It confirms in law that some people are regarded as better off dead and that our legal system, health professionals and care institutions will help to make them dead.

These laws separate us into two classes of people: those whose lives are considered sacred and whose deaths we invest heavily in preventing, and those who are considered dispensable and whose deaths we invest in assisting.

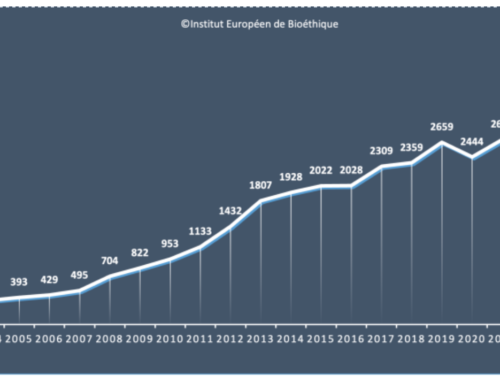

As time goes on and assisted suicide is normalised, this latter class of people expands. In Canada, for example, euthanasia was legalised in 2016.

Within 5 years, the class of those eligible expanded from the terminally ill to the chronically sick or disabled who are not dying, and the requirement of natural death being reasonably foreseeable was repealed.

In less than 18 months from now, eligibility will also extend to those suffering mental illness alone. In due course we can expect provision for the unconscious and children.

Many of those who have made submissions to this Committee have spoken of their own personal experience. I would like to speak briefly of my own.

In 2015, a sudden attack of Guillain-Barré Syndrome left me close to death, paralysed from the neck down, in extreme pain and reliant on others for every aspect of my existence for the next five months in hospital.

“IN ADDITION TO MY OWN ILLNESS AND THAT OF PEOPLE I LOVE, I HAVE MORE THAN THIRTY YEARS’ EXPERIENCE AS A PASTOR WALKING WITH THE SICK AND THEIR FATIGUED CARERS …”

My recovery was a very slow and painful process. I was embedded amongst patients suffering from multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease and other degenerative and ultimately fatal illnesses.

Although I recovered, I had an experience of the kind of suffering that makes some people want to end it all.

Both my parents are in nursing care and my mother is presently dying of bone marrow cancer. In addition to my own illness and that of people I love, I have more than thirty years’ experience as a pastor walking with the sick and their fatigued carers, sitting by the dying and offering love and hope, prayer and sacrament, and commending the dead to God while comforting their grieving families.

As difficult as these times have been, I have also witnessed the reconciliation and peace that comes with letting these things work themselves through.

So I approach these questions not just from theory or dogma but personal experience. Indeed, religious believers cannot approach this issue from a sanitised distance, as care of the sick and dying is core to our mission.

It is the reason why the Catholic Church is the oldest and largest provider of healthcare, aged care and palliative care in the world.

Those who seek to exclude religious voices from this discussion, or minimise the weight given them, are not only demonstrating anti-religious bias but also rejecting the views of one of the chief providers of end-of-life care.

I appreciate that the terms of reference for this inquiry do not address the fundamental question of whether NSW should cross the precipice of allowing some of its citizens to be killed or assisted to kill themselves. Instead we are asked to focus on the provisions of the bill before us.

These provisions are addressed in our submission in detail. However, it is worth noting that the bill lacks many of the safeguards in the bill presented to this Legislative Council just four years ago.

It also represents a serious attack on the freedom of religious hospitals and aged care facilities to operate in accordance with their ethos which the previous bill did not.

“IT IS THE SHORTEST INQUIRY INTO EUTHANASIA AND ASSISTED SUICIDE HELD IN ANY AUSTRALIAN JURISDICTION.”

I ask this Committee to consider seriously the amendments we have proposed.

Finally, it would be remiss of me not to record that this inquiry is the shortest in duration of any inquiry before this Committee—and perhaps any committee—in the history of the NSW Parliament.

It is the shortest inquiry into euthanasia and assisted suicide held in any Australian jurisdiction. It has allowed fewer submissions than any other state inquiry.

It is also being held at a time when our health professionals are fully occupied, even over-stretched, by the COVID pandemic and so have been unable to contribute as they might to the inquiry and broader debate.

Notwithstanding the incredibly short timeframe, I ask the Committee to consider carefully the many submissions before it and to ensure that the law does not put the already vulnerable even more at risk.