EDITORIAL

JEROME LEJEUNE: A DOCTOR FOR ALL SEASONS

Some of the best workers in healthcare have been faithful Catholics. We believe that our Faith, academic excellence and a robust defence of life from conception until natural death all go hand in hand. We describe here one such person whose research and clinical guidance changed the lives of so many, Professor Jerome Lejeune. He has directly influenced the work of the CMA: a specialist clinic for persons with Down syndrome was established and is run by members of the CMA and it is based at The Hospital of St John and St Elizabeth in London.

Jerome Lejeune was born in Montrouge, France, in 1926. A reading of The Country Doctor by the French novelist Balzac convinced him of his vocation when he was 13 years old. He too wanted to be a simple country doctor dedicating his life to helping the poor.

After attending medical school, he was persuaded by Professor Raymond Turpin to collaborate with him on a study of Down syndrome. He accepted this challenge and his dreams of being a simple country doctor were laid to rest.

He and his wife Birthe had five children and his family life and his faith were always his priority. When his beloved father was dying of lung cancer, he recognised more deeply the mystery of human suffering and the presence of Christ in all those who suffer.

In 1954, he was appointed a committee member of the French Genetics society and in 1957 was named an expert on the effects of atomic radiation on human genetics by the United Nations.

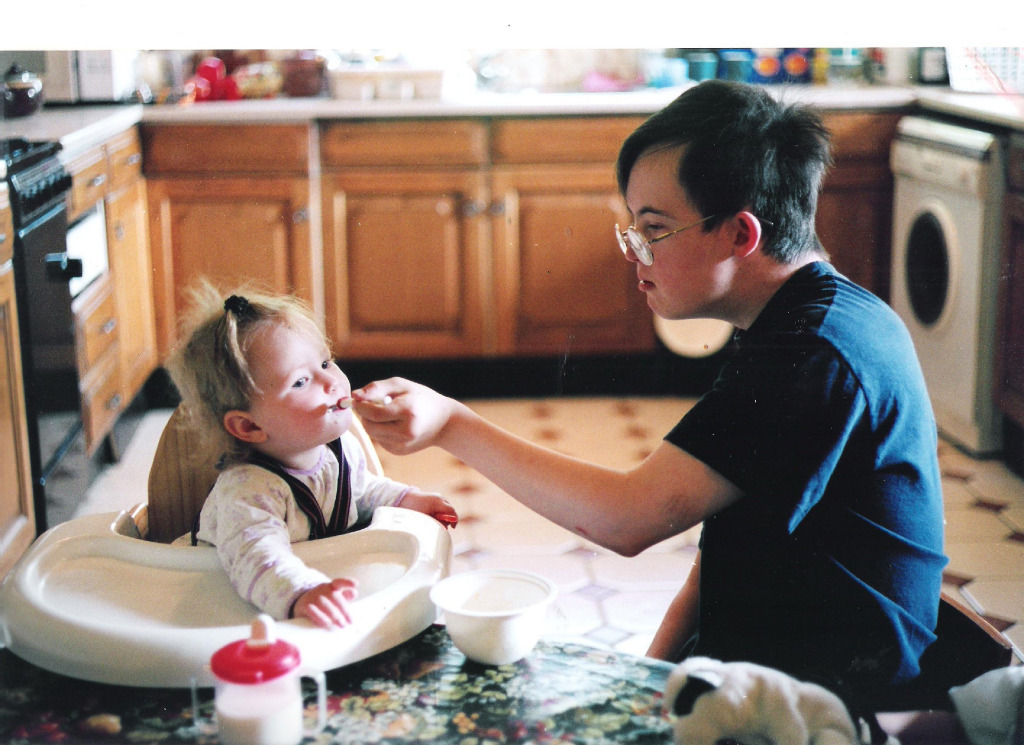

In 1959 he discovered the cause of Down syndrome and was also to diagnose the first case of Cri du Chat Syndrome. In 1962, he was awarded the prestigious Kennedy prize and, in 1965, he was appointed to the first Chair in Fundamental Genetics at the University of Paris. During this time, he helped thousands of parents to accept and love their children with Down syndrome.

Jerome Lejeune could easily have won the Nobel Prize. But he put his conscience above all worldly success and he committed himself to the pro-life cause when he realized that children with Down syndrome were being aborted in ever greater numbers.

“Today, I lost my Nobel Prize in Medicine.”

Lejeune was always deeply committed to his Catholic Faith and he lived an intense spiritual life. In 1967, he underwent a mystical experience when he visited a small chapel in the Holy Land. He experienced the presence of God with intensity and, at the same time, he realized that success and the opinion of others mattered little in comparison with the pursuit of truth.

And yet success came once again in 1969 when he was given the William Allen Memorial Award, the highest distinction that could be granted to a Geneticist. During his speech, he condemned abortion and later wrote to his wife: “Today, I lost my Nobel Prize in Medicine.”

In 1970, the French Parliament drafted a Bill that would allow pre-natal diagnosis and abortion for reasons of disability. Lejeune appeared on television and condemned this move. He received thousands of letters from patients with disabilities and also from parents of children with disabilities. In 1972 he wrote “For them (his pro-abortion medical colleagues) the foetus is no longer a person, a creature of God destined to see Him and love Him for all Eternity.” In 1973, a Bill to decriminalise abortion in France was filed. Lejeune and his wife collected thousands of signatures from French doctors and politicians against the measure and the bill failed. However, much to his dismay, a law allowing abortion was passed in 1974. His pro-life stance led to his research grants being withdrawn and he was forced to close his laboratory.

In 1991, he wrote a summary of his reflections on medical ethics for his fellow Catholics in seven brief points:

- Christians, be not afraid. It is you who possess the truth. Not that you invented it but because you are the vehicle for it. To all doctors, you must repeat: “you must conquer the illness, not attack the patient.”

- We are made in the image of God. For this reason alone all human beings must be respected.

- Abortion and infanticide are unspeakable crimes.

- Objective morality exists. It is clear and it is universal – because it is Catholic.

- The child is not disposable and marriage is indissoluble.

- “You shall honour your father and mother.” Therefore, uniparental reproduction by any means is always wrong.

- In so-called pluralistic societies, they shout it down our throats: “You Christians do not have the right to impose your morality on others.” Well, I tell you, not only do you have the right to try to incorporate your morality in the law but it is your democratic duty.

There is a famous story of an American physician who told Lejeune the following:

“My father was a Jewish physician in Braunau, Austria. One day only two babies were born at the local hospital. The parents of the healthy boy were proud and happy. The other was a girl (with Down syndrome) and her parents were sad.”

The physician ended the story by saying that the girl grew up to look after her mother despite her own disability. Her name is not known. The boy’s name was Adolph Hitler. Quite likely the story is apocryphal. However, it does express the truth that was central to Lejeune’s vocation: people with disabilities are certainly no less human than those without.

In 1993, Blessed Pope John Paul, his close friend, appointed Lejeune to be the first president of the Pontifical Academy for Life. That same year he was diagnosed with lung cancer and, by Good Friday of 1994, he was critically ill. “I have never betrayed my faith” he said. While reflecting on his patients, he was moved to tears and said: “I was supposed to have cured them…What will happen to them?”

A little later he was filled with joy. He said: “My children, if I can leave you with one message, this is the most important of all: We are in the hands of God. I have experienced this number of times.” He died the next day. Pope John Paul wrote of him: “We find ourselves today faced with the death of a great Christian of the twentieth century, a man for whom the defence of life had become an apostolate.” His cause for canonisation has been postulated. Our bishops have recently agreed on three priorities for the Church, one of which is to proclaim the coming of the Kingdom by supporting integrity in public life, cohesion and mutual respect in society and serving the marginalised and the vulnerable. May this great servant of God, an apostle of the vulnerable, be an example to us all.