IN PERSON | AUG. 23, 2017

These Daily Habits Will Make You Happier, Says Catholic Psychiatrist

Learn the pitfalls that can make you a grouch, and the practices that have brought joy to so many of the saints.

Joan Frawley Desmond

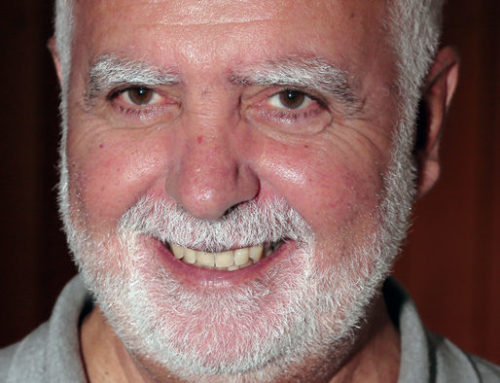

Dr. Aaron Kheriaty is an associate professor of psychiatry and the director of the bioethics program at the University of California-Irvine School of Medicine.

In an interview with Joan Frawley Desmond, a senior editor for the Register, he discussed psychological and medical research on the virtues, happiness and human flourishing.

Americans are told they have a right to “the pursuit of happiness,” yet research shows that anxiety and depression have skyrocketed. Is this the result of political or economic conditions, or is something else at work?

Political and economic circumstances, like the 2008 recession, certainly play a role in the rising rates of depression and anxiety. But if we look at the recent rise of what researchers Anne Case and Angus Deaton have called “deaths of despair” — deaths by suicide, drug overdoses and alcohol problems — we see that other important social and cultural factors are at work.

We live in a society in which people feel increasingly socially isolated. The breakdown of marriage and weakening of family ties have disproportionately affected those with lower socioeconomic status, who are already more vulnerable. Self-reported loneliness has doubled from 20% to 40% of Americans, who now say they don’t have a person in their life who can help support them in a difficult time, or with whom they can discuss important matters. If Americans have the right to pursue happiness, that cannot happen in a social vacuum. We need a society where solidarity is lived, and where social connections that contribute to human flourishing are facilitated.

What role does biology play in mental-health issues, like depression and anxiety?

Biological factors, such as genes, play a significant role in these disorders. Some people are born into the world with certain vulnerabilities based on biology or early developmental factors. Medical treatments for depression and anxiety can be important and even lifesaving in severe cases. As a psychiatrist, I prescribe antidepressants routinely, and they can be very helpful for some individuals.

But biological factors alone do not fully account for mental-health disorders; even serious conditions, like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, are not entirely explained by a person’s genes.

Today, we are seeing rising rates of depression and suicide, especially among young people. From a behavioral perspective, depression is a signal to withdraw from an environment that is perceived as dangerous or toxic. So in addition to looking at biology and brain chemistry, we also need to ask: What social and cultural factors are causing more and more people to withdraw into depressive states, or even to decide life is no longer worth living?

Judging from the acrimony of our national debates on social issues, isn’t there also real disagreement on what constitutes true happiness?

Indeed, there seem to be two competing views of what constitutes happiness. Some view happiness as the achievement of maximum pleasure, the optimal satisfaction of one’s desires — psychologists call this “hedonic happiness,” from the same word where we get “hedonism.” On this view of happiness, if I have a whim or an impulse to acquire something, and I attain what I want, it will make me feel good. Happiness is then a measure of my momentary contentment, and maximizing happiness means accumulating more such moments of satiation or satisfaction.

A richer and more complete notion of human happiness involves developing our talents, cultivating our most important relationships, and pursing excellence in our work — including activities in the home that contribute to the family and activities in society that contribute to the common good. This view of happiness requires that we cultivate and shape our desires such that we desire what is authentically good for us, what is really conducive to human flourishing. On this view, it makes sense to ask whether or not it is good for me to desire this or that, rather than simply taking our desires or impulses as a given. We shape our desires in the direction of authentic human goods — friendship, or professional excellence, for example — through the development of character strengths and virtues.

This richer conception of happiness also takes account of the fact that all of us will have rough patches in life, and that some degree of suffering is unavoidable. We will inevitably experience loss, illness, perhaps disability or dependency. Developing specific character traits and virtues, like resilience and fortitude, will help us weather those difficulties. On this view, the inevitability of suffering or hardship does not negate the possibility of happiness, though it does make the pursuit of happiness more challenging.

The virtues not only contribute to our happiness, they help us develop true freedom. We often think we are simply born free: “Freedom” means being entirely unconstrained, such that we can always get whatever we want. This is mistaken, and if taken to its extreme, this notion of freedom leads to the forms of enslavement seen with addictions. This false notion of freedom actually impairs our ability to really choose and pursue what is best for us.

So our happiness depends on recovering the challenge of true freedom?

True freedom is not just “freedom from,” but “freedom for” — it is the ability to pursue the good, even in the face of obstacles. Authentic interior freedom must be acquired and cultivated. On this understanding, our happiness will depend more on the kind of person we have become, rather than on external circumstances that are mostly outside of our control.

The idea that our character affects our ability to be happy is a key finding of the “positive psychology” movement.

That’s right. Some older schools of psychology take a deterministic view of our capacity for happiness: We are victims of our circumstances, entirely conditioned by internal or external factors that we do not choose; our past experience determines our future, or our genes determine our destiny.

By contrast, “positive psychology,” which was founded by Martin Seligman, shows that our present choices shape our experience of and capacity for happiness. The story goes that Seligman was working in his garden one day with his daughter, and he got upset with her for playing and making a mess there while he was trying to weed. She told him, “From the time I was 3 until I was 5, I whined a lot. But I decided the day I turned 5 to stop whining. And I haven’t whined once since the day I turned 5.” Then she challenged him, “Daddy, if I could stop whining, you can stop being such a grouch.”

In this encounter, Seligman realized that if he knew anything about developing kindness or other virtues, this was not from his study of psychology. Experts in his field had spent much of their time studying what can go wrong in our mental life — psychological disorders, mental disease or neurosis — but had neglected to rigorously study the traits that foster mental health and human flourishing. He launched the positive-psychology movement to remedy this.

Seligman discovered that the practice of virtue promotes happiness, correct?

That’s right. And when Seligman and Christopher Peterson wrote Character Strengths and Virtues, the influential handbook of positive psychology, their psychological, cross-cultural and historical research led them to divide their book into seven major virtues that were essential for mental health and human flourishing. This list turned out to be a recapitulation of the classical cardinal virtues: justice, courage (fortitude), prudence (practical wisdom) and temperance. They also identified important traits that Christians would equate with the theological virtues — what the positive psychologists called transcendence and humanity, which include virtues such as gratitude, hope, spirituality and love.

How does gratitude make us happy?

Robert Emmons, a professor of psychology at the University of California at Davis, has researched and documented the many psychological and physical benefits of practicing gratitude. He found that the practice of cultivating gratitude toward God and other people — even a simple daily exercise, like writing down three things you feel grateful for — can have profoundly positive effects on our mental health, such as diminishing depression and anxiety.

As Christians, we know how central gratitude and forgiveness are to the biblical account of the human person and Our Lord’s own teachings, so these findings are not surprising.

What about forgiveness?

When we have really been hurt by people, forgiveness can require heroic effort; indeed, it may even require God’s grace and supernatural assistance. Richard Fitzgibbons, co-author of Forgiveness Therapy, found that the practice of forgiveness and relinquishing anger — even in the face of injustice or mistreatment — improves our mental health and fosters sustained levels of happiness. Forgiveness is profoundly healing, not only for the recipient, but for the person who practices this virtue.

Today, we seem to have more difficulty forgiving our enemies. Personal attacks and public shaming on social media — often to enforce a regime of political correctness — is on the rise.

Indeed, these negative trends undermine a truly integrated vision of human flourishing. We are seeing a counterfeit substitute for virtue and social solidarity, with concern for the common good devolving into power games that advance the interests of my tribe or identity group. This is not conducive to the health and flourishing of the people who take part in such activities, nor does it promote the kind of social solidarity that helps people grow in a healthy way.

Before posting a comment online, a tweet or a “reply all” email, we can ask ourselves the question: Would I say this same thing if the recipient was sitting here with me face-to-face? People say all kinds of things on social media that they would never dream of saying directly to a person present. This simple criterion can help us foster civil discourse, which should always be characterized by humility and respect for those with whom we disagree. What is more, online social media is no substitute for real personal encounters. A bit of “electronic fasting” from our smartphones and other screens from time to time would go a long way toward improving our mental health.

You have talked about good stress and bad stress. How does stress affect our happiness?

Good stress is always short term and focused on a clear objective; a bit of this sort of stress (say, a deadline to complete a project) can spur you on and actually make you more productive. It motivates you to sit down at the computer and knock out that report.

Bad stress is chronic, long-term and diffuse — not focused on a clear and realizable objective. This kind of stress makes you less productive. If I am chronically behind on deadlines, or if I simply have too much coming at me at once, I am going to slide into a state of chronic stress and that will produce wear and tear on my body and adversely impact my mental health.

The stress response is designed to help us operate at a higher level for shorter period of time. But the body can only stay in a hypervigilant state for so long before this impairs our functioning.

Today, many practicing Catholics work through Sunday, once understood and respected as “the day of rest.” Is that contributing to stress and anxiety?

Yes. The notion of the “Sabbath” rest is receding, and work has begun to creep into all aspects of our life, as technology has become increasingly intrusive. We have to push back against this.

The author Walker Percy observed that Americans have a tendency to oscillate between intense, frenetic activity on the one hand and flabby, wasteful inactivity on the other. He called these two tendencies “angelism-bestialism”: We behave like disembodied angels that have no physical needs, working 18 hours a day for 10 days in a row. Then we crash and vegetate in front of the television, binge-watching reruns and overeating to compensate for our exhaustion.

Real Sabbath rest is literally re-creation, taking part in activities that require less effort and that renew and refresh us. Authentic leisure, Sabbath rest, connects us with other people and with God. It restores a balance to our life.

What are the basic elements of a balanced spiritual life?

The Catholic tradition is rich with spiritual practices that we can integrate into the days and seasons of our life. We should not try to reinvent the wheel here.

Daily: prayer, spiritual reading and Mass whenever possible

Weekly: Sabbath rest

Monthly: spiritual direction, confession, support group

Yearly: retreat (preferably silent)

It’s good to pick a few of these norms of piety that will help you develop your spiritual life. Practice them well and consistently, and make them part of the fabric of your day. Protect the time you have set aside for these, and prioritize them. This may include 10-15 minutes of mental prayer in the morning or evening that allows us to be conversation with Christ. When you feel dry or distracted, bring a book. Ten minutes a day of reading the New Testament or a spiritual classic will give you content for your prayer and things to work on. When it’s hard to focus on mental prayer, recitation of the Rosary and consideration of the mysteries is helpful. This is a wonderful daily habit recommended by many of the saints, and there is some interesting research on its calming and anxiety-reducing effects.

Consider also the practice of attending daily Mass or Eucharistic adoration. The psychological as well as spiritual benefits of regular confession are considerable. It is very beneficial to go at least every month; if you wait longer, it can be hard to remember what has transpired, and it’s easy to grow lukewarm.

Some people find it helpful to go to the same priest to deepen the quality of the guidance they receive. If you pick two or three of these traditional practices and integrate them into your routine, you will begin to see their transformative effects.

Does a strong spiritual life help us gradually discard ersatz forms of happiness and guide our search for true happiness?

Alexis de Tocqueville observed [in Democracy in America] that Americans paradoxically appeared to be chronically restless and dissatisfied, even in the midst of great material abundance. We need more than economic prosperity, more than just the satisfaction of material or bodily needs, to find authentic happiness and fulfillment.

There’s a substantial and growing body of medical and social-science research suggesting that, on the whole, spiritual and religious practices are conducive to health and human flourishing. Some people will bristle at this suggestion, but the evidence is quite robust.

St. Augustine famously said that God has created us for himself, and our hearts are restless until they rest in him. This is an expression of the Christian claim that true happiness can ultimately be found only in union with God. Our Catholic faith speaks precisely to this deep human need in the most profoundly human way.

Joan Frawley Desmond is a Register senior editor.

http://www.ncregister.com/

http://www.ncregister.com/