By Agnieszka Krawczynski

The Archbishop of Vancouver has added his voice to the booming sound of local leaders calling for an end to B.C.’s opioid overdose crisis.

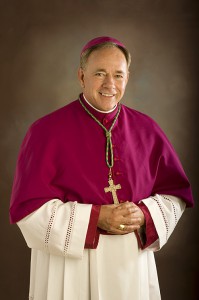

“This health emergency is widespread, cutting across every segment of society and devastating families and communities,” wrote Archbishop J. Michael Miller, CSB, in a pastoral letter to local Catholics Feb. 16.

“It is claiming the lives of people on the street and those struggling with mental illness and trauma. It is killing our youth, students, workers, and elderly. Sadly, many of those who survive suffer brain damage and from other long-term consequences.”

More than 900 B.C. residents died from overdoses in 2016. That death toll included 215 lives lost in Vancouver and 108 in Surrey.

“On average, a life is taken every 10 hours – more than double the number of homicides and traffic fatalities combined. And the situation is not getting better,” he said.

St. Paul’s Hospital, a Catholic institution run by Providence Health Care, is “particularly affected.” Emergency staff at that downtown hospital dealt with 42 overdoses between Christmas and New Year’s Day alone.

B.C. government statistics show 142 people died of a drug overdose in December alone, the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in one month in B.C., beating the previous month’s record of 128.

“Everyone feels the impact: from emergency room personnel, to hospital staff, to health-care workers at all levels,” Archbishop Miller wrote.

“The toll is especially brutal on first responders who find themselves physically and mentally exhausted by their exceptionally difficult job.”

A January report from the City of Vancouver shows that downtown Firehall #2 received 2,211 calls about overdoses in 2016, compared to 804 in 2015 (a 175 per cent increase). Nearby Firehall #1 experienced a 115 per cent jump in emergency overdose calls in 2016.

The government has called the overdose crisis a public health emergency and on Jan.25 the City of Vancouver approved a plan to spend $2.2 million to address the crisis.

As public officials, emergency workers, and volunteers scramble to reach out, Archbishop Miller suggests several ways Catholics can help.

“We recognize in this scourge a pressing call to see the face of Jesus in those who suffer and those who are tragically claimed by lethal drug overdoses,” he wrote.

“I am inviting the Church in Vancouver to respond to the overdose crisis by reaching out to our society’s suffering men, women, and young people.”

Before offering specific recommendations, Archbishop Miller reflects on some of the reasons people turn to the use and abuse of opioids.

One of the “most salient challenges” many B.C. residents face is social isolation.

“Social relationships in the community, which are the foundation of every society, are breaking down because an excessively individualistic worldview prevails in many quarters,” he wrote.

Lonely people coping with psychological and physical pain that may be compounded by poverty, economic instability, or broken family ties, may turn to drug use.

“On the other hand, when communities are welcoming and people know one another and feel as if they belong to a broader group, crime rates drop, as do levels of depression and suicide.”

Archbishop Miller, acknowledging contributions from Providence Health Care in drafting his letter, also points out a problem of over-prescribing opioids and the need to reach out to people with mental illness.

He said opioids are prescribed in North America at least six times more than in Europe. Patients facing acute and chronic pain may become dependent on these drugs and turn to the streets when they can’t get them elsewhere.

The health-care system must get to work “finding new ways” to deal with acute and chronic pain.

Meanwhile, more than half of people who seek help with addiction have a mental illness. This makes them particularly vulnerable, wrote the archbishop.

“People who suffer from mental illness need our help, our friendship, our outreach, our resources, and our prayer. We can assume our responsibility by educating ourselves and others about this mental health crisis and its causes.”

About 20 per cent of Canadians experience some kind of mental illness.

Archbishop Miller called on the faithful to “imitate Christ the Healer,” “stamp out the stigma” of mental illness, and make people struggling with mental illness or addiction feel welcome in Catholic parishes, schools, and communities.

Pope Francis has voiced a similar message: “We cannot stoop to the injustice of categorizing drug addicts as if they were mere objects or broken machines; each person must be valued and appreciated in his or her dignity in order to enable them to be healed.”

Archbishop Miller also called for better access to psychological and psychiatric help for young people. With a provincial election coming in the spring, he said this is the time to make addiction and mental health issues political.

The emergency ward at St. Paul’s Hospital treats 43 per cent of Lower Mainland patients with the most severe mental health issues, he said, and it’s critical that Catholic groups and individuals find ways to reach out.

“The Church’s response to the overdose crisis must imitate that of Jesus, who told us: ‘Whatever you do to the least of my brothers and sisters, you do unto me.’ He identified himself with those who in His day were in need: the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the naked, the sick, and the incarcerated,” he wrote.

“In 2017 Vancouver, Jesus would also identify Himself with those afflicted by mental illness and addiction. As His disciples, we are called to do likewise.”

The pastoral letter is online at http://rcav.org/l-overdosecrisis.