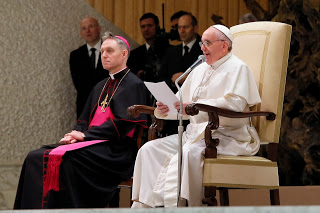

ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS POPE FRANCIS

TO THE MEMBERS OF THE DIPLOMATIC CORPS ACCREDITED TO THE HOLY SEE

FOR THE TRADITIONAL EXCHANGE OF NEW YEAR GREETINGS

Regia Hall

Monday, 8 January 2018

Your Excellencies,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Our meeting today is a welcome tradition that allows me, in the enduring joy of the Christmas season, to offer you my personal best wishes for the New Year just begun, and to express my closeness and affection to the peoples you represent. I thank the Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, His Excellency Armindo Fernandes do Espírito Santo Vieira, Ambassador of Angola, for his respectful greeting on behalf of the entire Diplomatic Corps accredited to the Holy See. I offer a particular welcome to the non-resident Ambassadors, whose numbers have increased following the establishment last May of diplomatic relations with the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. I likewise greet the growing number of Ambassadors resident in Rome, which now includes the Ambassador of the Republic of South Africa. I would like in a special way to remember the late Ambassador of Colombia, Guillermo León Escobar-Herrán, who passed away just a few days before Christmas. I thank all of you for your continuing helpful contacts with the Secretariat of State and the other Dicasteries of the Roman Curia, which testify to the interest of the international community in the Holy See’s mission and the work of the Catholic Church in your respective countries. This is also the context for the Holy See’s pactional activities, which last year saw the signing, in February, of the Framework Agreement with the Republic of the Congo, and, in August, of the Agreement between the Secretariat of State and the Government of the Russian Federation enabling the holders of diplomatic passports to travel without a visa.

In its relations with civil authorities, the Holy See seeks only to promote the spiritual and material well-being of the human person and to pursue the common good. The Apostolic Journeys that I made during the course of the past year to Egypt, Portugal, Colombia, Myanmar and Bangladesh were expressions of this concern. I travelled as a pilgrim to Portugal on the centenary of the apparitions of Our Lady of Fatima, to celebrate the canonization of the shepherd children Jacinta and Francisco Marto. There I witnessed the enthusiastic and joyful faith that the Virgin Mary roused in the many pilgrims assembled for the occasion. In Egypt, Myanmar and Bangladesh too, I was able to meet the local Christian communities that, though small in number, are appreciated for their contribution to development and fraternal coexistence in those countries. Naturally, I also had meetings with representatives of other religions, as a sign that our differences are not an obstacle to dialogue, but rather a vital source of encouragement in our common desire to know the truth and to practise justice. Finally, in Colombia I wished to bless the efforts and the courage of that beloved people, marked by a lively desire for peace after more than half a century of internal conflict.

Dear Ambassadors,

This year marks the centenary of the end of the First World War, a conflict that reconfigured the face of Europe and the entire world with the emergence of new states in place of ancient empires. From the ashes of the Great War, we can learn two lessons that, sad to say, humanity did not immediately grasp, leading within the space of twenty years to a new and even more devastating conflict. The first lesson is that victory never means humiliating a defeated foe. Peace is not built by vaunting the power of the victor over the vanquished. Future acts of aggression are not deterred by the law of fear, but rather by the power of calm reason that encourages dialogue and mutual understanding as a means of resolving differences.[1] This leads to a second lesson: peace is consolidated when nations can discuss matters on equal terms. This was grasped a hundred years ago – on this very date – by the then President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, who proposed the establishment of a general league of nations with the aim of promoting for all states, great and small alike, mutual guarantees of independence and territorial integrity. This laid the theoretical basis for that multilateral diplomacy, which has gradually acquired over time an increased role and influence in the international community as a whole.

Relations between nations, like all human relationships, “must likewise be harmonized in accordance with the dictates of truth, justice, willing cooperation, and freedom”.[2] This entails “the principle that all states are by nature equal in dignity”,[3] as well as the acknowledgment of one another’s rights and the fulfilment of their respective duties.[4] The basic premise of this approach is the recognition of the dignity of the human person, since disregard and contempt for that dignity resulted in barbarous acts that have outraged the conscience of mankind.[5] Indeed, as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms, “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world”.[6]

I would like to devote our meeting today to this important document, seventy years after its adoption on 10 December 1948 by the General Assembly of the United Nations. For the Holy See, to speak of human rights means above all to restate the centrality of the human person, willed and created by God in his image and likeness. The Lord Jesus himself, by healing the leper, restoring sight to the blind man, speaking with the publican, saving the life of the woman caught in adultery and demanding that the injured wayfarer be cared for, makes us understand that every human being, independent of his or her physical, spiritual or social condition, is worthy of respect and consideration. From a Christian perspective, there is a significant relation between the Gospel message and the recognition of human rights in the spirit of those who drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Those rights are premised on the nature objectively shared by the human race. They were proclaimed in order to remove the barriers that divide the human family and to favour what the Church’s social doctrine calls integral human development, since it entails fostering “the development of each man and of the whole man… and humanity as a whole”.[7] A reductive vision of the human person, on the other hand, opens the way to the growth of injustice, social inequality and corruption.

It should be noted, however, that over the years, particularly in the wake of the social upheaval of the 1960’s, the interpretation of some rights has progressively changed, with the inclusion of a number of “new rights” that not infrequently conflict with one another. This has not always helped the promotion of friendly relations between nations,[8] since debatable notions of human rights have been advanced that are at odds with the culture of many countries; the latter feel that they are not respected in their social and cultural traditions, and instead neglected with regard to the real needs they have to face. Somewhat paradoxically, there is a risk that, in the very name of human rights, we will see the rise of modern forms of ideological colonization by the stronger and the wealthier, to the detriment of the poorer and the most vulnerable. At the same time, it should be recalled that the traditions of individual peoples cannot be invoked as a pretext for disregarding the due respect for the fundamental rights proclaimed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

At a distance of seventy years, it is painful to see how many fundamental rights continue to be violated today. First among all of these is the right of every human person to life, liberty and personal security.[9] It is not only war or violence that infringes these rights. In our day, there are more subtle means: I think primarily of innocent children discarded even before they are born, unwanted at times simply because they are ill or malformed, or as a result of the selfishness of adults. I think of the elderly, who are often cast aside, especially when infirm and viewed as a burden. I think of women who repeatedly suffer from violence and oppression, even within their own families. I think too of the victims of human trafficking, which violates the prohibition of every form of slavery. How many persons, especially those fleeing from poverty and war, have fallen prey to such commerce perpetrated by unscrupulous individuals?

Defending the right to life and physical integrity also means safeguarding the right to health on the part of individuals and their families. Today this right has assumed implications beyond the original intentions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which sought to affirm the right of every individual to receive medical care and necessary social services.[10] In this regard, it is my hope that efforts will be made within the appropriate international forums to facilitate, in the first place, ready access to medical care and treatment on the part of all. It is important to join forces in order to implement policies that ensure, at affordable costs, the provision of medicines essential for the survival of those in need, without neglecting the area of research and the development of treatments that, albeit not financially profitable, are essential for saving human lives.

Defending the right to life also entails actively striving for peace, universally recognized as one of the supreme values to be sought and defended. Yet serious local conflicts continue to flare up in various parts of the world. The collective efforts of the international community, the humanitarian activities of international organizations and the constant pleas for peace rising from lands rent by violence seem to be less and less effective in the face of war’s perverse logic. This scenario cannot be allowed to diminish our desire and our efforts for peace. For without peace, integral human development becomes unattainable.

Integral disarmament and integral development are intertwined. Indeed, the quest for peace as a precondition for development requires battling injustice and eliminating, in a non-violent way, the causes of discord that lead to wars. The proliferation of weapons clearly aggravates situations of conflict and entails enormous human and material costs that undermine development and the search for lasting peace. The historic result achieved last year with the adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons at the conclusion of the United Nations Conference for negotiating a legally binding instrument to ban nuclear arms, shows how lively the desire for peace continues to be. The promotion of a culture of peace for integral development calls for unremitting efforts in favour of disarmament and the reduction of recourse to the use of armed force in the handling of international affairs. I would therefore like to encourage a serene and wide-ranging debate on the subject, one that avoids polarizing the international community on such a sensitive issue. Every effort in this direction, however modest, represents an important step for mankind.

For its part, the Holy See signed and ratified, also in the name of and on behalf of Vatican City State, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. It did so in the belief, expressed by Saint John XXIII in Pacem in Terris, that “justice, right reason, and the recognition of man’s dignity cry out insistently for a cessation to the arms race. The stockpiles of armaments which have been built up in various countries must be reduced all round and simultaneously by the parties concerned. Nuclear weapons must be banned”.[11] Indeed, even if “it is difficult to believe that anyone would dare to assume responsibility for initiating the appalling slaughter and destruction that war would bring in its wake, there is no denying that the conflagration could be started by some chance and unforeseen circumstance”.[12]

The Holy See therefore reiterates the firm conviction “that any disputes which may arise between nations must be resolved by negotiation and agreement, not by recourse to arms”.[13] The constant production of ever more advanced and “refined” weaponry, and dragging on of numerous conflicts – what I have referred to as “a third world war fought piecemeal” – lead us to reaffirm Pope John’s statement that “in this age which boasts of its atomic power, it no longer makes sense to maintain that war is a fit instrument with which to repair the violation of justice… Nevertheless, we are hopeful that, by establishing contact with one another and by a policy of negotiation, nations will come to a better recognition of the natural ties that bind them together as men. We are hopeful, too, that they will come to a fairer realization of one of the cardinal duties deriving from our common nature: namely, that love, not fear, must dominate the relationships between individuals and between nations. It is principally characteristic of love that it draws men together in all sorts of ways, sincerely united in the bonds of mind and matter; and this is a union from which countless blessings can flow”.[14]

In this regard, it is of paramount importance to support every effort at dialogue on the Korean peninsula, in order to find new ways of overcoming the current disputes, increasing mutual trust and ensuring a peaceful future for the Korean people and the entire world.

It is also important for the various peace initiatives aimed at helping Syria to continue, in a constructive climate of growing trust between the parties, so that the lengthy conflict that has caused such immense suffering can finally come to an end. Our shared hope is that, after so much destruction, the time for rebuilding has now come. Yet even more than rebuilding material structures, it is necessary to rebuild hearts, to re-establish the fabric of mutual trust, which is the essential prerequisite for the flourishing of any society. There is a need, then, to promote the legal, political and security conditions that restore a social life where every citizen, regardless of ethnic and religious affiliation, can take part in the development of the country. In this regard, it is vital that religious minorities be protected, including Christians, who for centuries have made an active contribution to Syria’s history.

It is likewise important that the many refugees who have found shelter and refuge in neighbouring countries, especially in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, be able to return home. The commitment and efforts made by these countries in this difficult situation deserve the appreciation and support of the entire international community, which is also called upon to create the conditions for the repatriation of Syrian refugees. This effort must concretely start with Lebanon, so that that beloved country can continue to be a “message” of respect and coexistence, and a model to imitate, for the whole region and for the entire world.

The desire for dialogue is also necessary in beloved Iraq, to enable its various ethnic and religious groups to rediscover the path of reconciliation and peaceful coexistence and cooperation. Such is the case too in Yemen and other parts of the region, and in Afghanistan.

I think in particular of Israelis and Palestinians, in the wake of the tensions of recent weeks. The Holy See, while expressing sorrow for the loss of life in recent clashes, renews its pressing appeal that every initiative be carefully weighed so as to avoid exacerbating hostilities, and calls for a common commitment to respect, in conformity with the relevant United Nations Resolutions, the status quo of Jerusalem, a city sacred to Christians, Jews and Muslims. Seventy years of confrontation make more urgent than ever the need for a political solution that allows the presence in the region of two independent states within internationally recognized borders. Despite the difficulties, a willingness to engage in dialogue and to resume negotiations remains the clearest way to achieving at last a peaceful coexistence between the two peoples.

In national contexts, too, openness and availability to encounter are essential. I think especially of Venezuela, which is experiencing an increasingly dramatic and unprecedented political and humanitarian crisis. The Holy See, while urging an immediate response to the primary needs of the population, expresses the hope that conditions will be created so that the elections scheduled for this year can resolve the existing conflicts, and enable people to look to the future with newfound serenity.

Nor can the international community overlook the suffering of many parts of the African continent, especially in South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, Nigeria and the Central African Republic, where the right to life is threatened by the indiscriminate exploitation of resources, terrorism, the proliferation of armed groups and protracted conflicts. It is not enough to be appalled at such violence. Rather, everyone, in his or her own situation, should work actively to eliminate the causes of misery and build bridges of fraternity, the fundamental premise for authentic human development.

A shared commitment to rebuilding bridges is also urgent in Ukraine. The year just ended reaped new victims in the conflict that afflicts the country, continuing to bring great suffering to the population, particularly to families who live in areas affected by the war and have lost their loved ones, not infrequently the elderly and children.

I would like to devote a special thought to families. The right to form a family, as a “natural and fundamental group unit of society… is entitled to protection by society and the state”,[15] and is recognized by the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Unfortunately, it is a fact that, especially in the West, the family is considered an obsolete institution. Today fleeting relationships are preferred to the stability of a definitive life project. But a house built on the sand of frail and fickle relationships cannot stand. What is needed instead is a rock on which to build solid foundations. And this rock is precisely that faithful and indissoluble communion of love that joins man and woman, a communion that has an austere and simple beauty, a sacred and inviolable character and a natural role in the social order.[16] I consider it urgent, then, that genuine policies be adopted to support the family, on which the future and the development of states depend. Without this, it is not possible to create societies capable of meeting the challenges of the future. Disregard for families has another dramatic effect – particularly present in some parts of the world – namely, a decline in the birth rate. We are experiencing a true demographic winter! This is a sign of societies that struggle to face the challenges of the present, and thus become ever more fearful of the future, with the result that they close in on themselves.

At the same time, we cannot forget the situation of families torn apart by poverty, war and migration. All too often, we see with our own eyes the tragedy of children who, unaccompanied, cross the borders between the south and the north of our world, and often fall victim to human trafficking.

Today there is much talk about migrants and migration, at times only for the sake of stirring up primal fears. It must not be forgotten that migration has always existed. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the history of salvation is essentially a history of migration. Nor should we forget that freedom of movement, for example, the ability to leave one’s own country and to return there, is a fundamental human right.[17]There is a need, then, to abandon the familiar rhetoric and start from the essential consideration that we are dealing, above all, with persons.

This is what I sought to reiterate in my Message for the World Day of Peace celebrated on 1 January last, whose theme this year is: “Migrants and Refugees: Men and Women in Search of Peace”. While acknowledging that not everyone is always guided by the best of intentions, we must not forget that the majority of migrants would prefer to remain in their homeland. Instead, they find themselves “forced by discrimination, persecution, poverty and environmental degradation” to leave it behind… “Welcoming others requires concrete commitment, a network of assistance and good will, vigilant and sympathetic attention, the responsible management of new and complex situations that at times compound numerous existing problems, to say nothing of resources, which are always limited. By practising the virtue of prudence, government leaders should take practical measures to welcome, promote, protect, integrate and, ‘within the limits allowed by a correct understanding of the common good, to permit [them] to become part of a new society’ (Pacem in Terris, 57). Leaders have a clear responsibility towards their own communities, whose legitimate rights and harmonious development they must ensure, lest they become like the rash builder who miscalculated and failed to complete the tower he had begun to construct” (cf. Lk 14:28-30).[18]

I would like once more to thank the authorities of those states who have spared no effort in recent years to assist the many migrants arriving at their borders. I think above all of the efforts made by more than a few countries in Asia, Africa and the Americas that welcome and assist numerous persons. I cherish vivid memories of my meeting in Dhaka with some members of the Rohingya people, and I renew my sentiments of gratitude to the Bangladeshi authorities for the assistance provided to them on their own territory.

I would also like to express particular gratitude to Italy, which in these years has shown an open and generous heart and offered positive examples of integration. It is my hope that the difficulties that the country has experienced in these years, and whose effects are still felt, will not lead to forms of refusal and obstruction, but instead to a rediscovery of those roots and traditions that have nourished the rich history of the nation and constitute a priceless treasure offered to the whole world. I likewise express my appreciation for the efforts made by other European states, particularly Greece and Germany. Nor must it be forgotten that many refugees and migrants seek to reach Europe because they know that there they will find peace and security, which for that matter are the fruit of a lengthy process born of the ideals of the Founding Fathers of the European project in the aftermath of the Second World War. Europe should be proud of this legacy, grounded on certain principles and a vision of man rooted in its millenary history, inspired by the Christian conception of the human person. The arrival of migrants should spur Europe to recover its cultural and religious heritage, so that, with a renewed consciousness of the values on which the continent was built, it can keep alive her own tradition while continuing to be a place of welcome, a herald of peace and of development.

In the past year, governments, international organizations and civil society have engaged in discussions about the basic principles, priorities and most suitable means for responding to movements of migration and the enduring situations involving refugees. The United Nations, following the 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, has initiated important preparations for the adoption of the two Global Compacts for refugees and for safe, orderly and regular migration respectively.

The Holy See trusts that these efforts, with the negotiations soon to begin, will lead to results worthy of a world community growing ever more independent and grounded in the principles of solidarity and mutual assistance. In the current international situation, ways and means are not lacking to ensure that every man and every woman on earth can enjoy living conditions worthy of the human person.

In the Message for this year’s World Day of Peace, I suggested four “mileposts” for action: welcoming, protecting, promoting and integrating.[19] I would like to dwell particularly on the last of these, which has given rise to various opposed positions in the light of varying evaluations, experiences, concerns and convictions. Integration is a “two-way process”, entailing reciprocal rights and duties. Those who welcome are called to promote integral human development, while those who are welcomed must necessarily conform to the rules of the country offering them hospitality, with respect for its identity and values. Processes of integration must always keep the protection and advancement of persons, especially those in situations of vulnerability, at the centre of the rules governing various aspects of political and social life.

The Holy See has no intention of interfering in decisions that fall to states, which, in the light of their respective political, social and economic situations, and their capacities and possibilities for receiving and integrating, have the primary responsibility for accepting newcomers. Nonetheless, the Holy See does consider it its role to appeal to the principles of humanity and fraternity at the basis of every cohesive and harmonious society. In this regard, its interaction with religious communities, on the level of institutions and associations, should not be forgotten, since these can play a valuable supportive role in assisting and protecting, in social and cultural mediation, and in pacification and integration.

Among the human rights that I would also like to mention today is the right to freedom of thought, conscience and of religion, including the freedom to change religion.[20] Sad to say, it is well-known that the right to religious freedom is often disregarded, and not infrequently religion becomes either an occasion for the ideological justification of new forms of extremism or a pretext for the social marginalization of believers, if not their downright persecution. The condition for building inclusive societies is the integral comprehension of the human person, who can feel himself or herself truly accepted when recognized and accepted in all the dimensions that constitute his or her identity, including the religious dimension.

Finally, I wish to recall the importance of the right to employment. There can be no peace or development if individuals are not given the chance to contribute personally by their own labour to the growth of the common good. Regrettably, in many parts of the world, employment is scarcely available. At times, few opportunities exist, especially for young people, to find work. Often it is easily lost not only due to the effects of alternating economic cycles, but to the increasing use of ever more perfect and precise technologies and tools that can replace human beings. On the one hand, we note an inequitable distribution of the work opportunities, while on the other, a tendency to demand of labourers an ever more pressing pace. The demands of profit, dictated by globalization, have led to a progressive reduction of times and days of rest, with the result that a fundamental dimension of life has been lost – that of rest – which serves to regenerate persons not only physically but also spiritually. God himself rested on the seventh day; he blessed and consecrated that day “because on it he rested from all the work that he had done in creation” (Gen 2:3). In the alternation of exertion and repose, human beings share in the “sanctification of time” laid down by God and ennoble their work, saving it from constant repetition and dull daily routine.

A cause for particular concern are the data recently published by the International Labour Organization regarding the increase of child labourers and victims of the new forms of slavery. The scourge of juvenile employment continues to compromise gravely the physical and psychological development of young people, depriving them of the joys of childhood and reaping innocent victims. We cannot think of planning a better future, or hope to build more inclusive societies, if we continue to maintain economic models directed to profit alone and the exploitation of those who are most vulnerable, such as children. Eliminating the structural causes of this scourge should be a priority of governments and international organizations, which are called to intensify efforts to adopt integrated strategies and coordinated policies aimed at putting an end to child labour in all its forms.

Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

In recalling some of the rights contained in the 1948 Universal Declaration, I do not mean to overlook one of its important aspects, namely, the recognition that every individual also has duties towards the community, for the sake of “meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society”.[21] The just appeal to the rights of each human being must take into account the fact that every individual is part of a greater body. Our societies too, like every human body, enjoy good health if each member makes his or her own contribution in the awareness that it is at the service of the common good.

Among today’s particularly pressing duties is that of caring for our earth. We know that nature can itself be cruel, even apart from human responsibility. We saw this in the past year with the earthquakes that struck different parts of our world, especially those of recent months in Mexico and in Iran, with their high toll of victims, and with the powerful hurricanes that struck different countries of the Caribbean, also reaching the coast of the United States, and, more recently, the Philippines. Even so, one must not downplay the importance of our own responsibility in interaction with nature. Climate changes, with the global rise in temperatures and their devastating effects, are also a consequence of human activity. Hence there is a need to take up, in a united effort, the responsibility of leaving to coming generations a more beautiful and livable world, and to work, in the light of the commitments agreed upon in Paris in 2015, for the reduction of gas emissions that harm the atmosphere and human health.

The spirit that must guide individuals and nations in this effort can be compared to that of the builders of the medieval cathedrals that dot the landscape of Europe. These impressive buildings show the importance of each individual taking part in a work that transcends the limits of time. The builders of the cathedrals knew that they would not see the completion of their work. Yet they worked diligently, in the knowledge that they were part of a project that would be left to their children to enjoy. These, in turn, would embellish and expand it for their own children. Each man and woman in this world – particularly those with governmental responsibilities – is called to cultivate the same spirit of service and intergenerational solidarity, and in this way to be a sign of hope for our troubled world.

With these thoughts, I renew to each of you, to your families and to your peoples, my prayerful good wishes for a year filled with joy, hope and peace. Thank you.

[1] Cf. JOHN XXIII, Encyclical Letter Pacem in Terris, 11 April 1963, 90.

[2] Ibid., 80.

[3] Ibid., 86.

[4] Ibid., 91.

[5]Cf. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 10 December 1948.

[6] Ibid. Preamble.

[7] PAUL VI, Encyclical Letter Populorum Progressio, 26 March 1967, 14.

[8] Cf. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Preamble.

[9] Cf. ibid., Art.3.

[10] Cf. ibid., Art. 25.

[11] Pacem in Terris, 112.

[12] Ibid., 111.

[13] Ibid., 126.

[14] Ibid., 127 and 129.

[15] Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Art. 16.

[16] Cf. PAUL VI, Address in the Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth, 5 January 1964.

[17] Cf. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Art. 13.

[18] FRANCIS, Message for the 2018 World Day of Peace, 13 November 2017, 1.

[19] Ibid., 4.

[20] Cf. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Art. 18.

[21]Ibid., Art. 29.

…………………………

http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/it/events/event.dir.html/content/vaticanevents/it/2018/1/8/corpo-diplomatico.html

http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/it/events/event.dir.html/content/vaticanevents/it/2018/1/8/corpo-diplomatico.html